The Halifax Explosion

November 3, 2017 by Rachel

Over a hundred years ago, my grandmother came to this country on a blueberry boat. As a very young child, I imagined a boat, amassed of giant blueberries, bobbing across the ocean waves: as I grew older I realized the boat was only called that because it carried blueberries over from Nova Scotia to Boston.

My grandmother came to this country on a blueberry boat, but that’s all I have of the story. My grandmother was a restless and dissatisfied woman, as was my mother. We drove down to visit my grandmother almost every weekend. After a quick family meal together, my father took my siblings on mysteriously long walks, which I suspected included visits to the candy store, the beach, and the park where the swans lived. I was left in my grandmother’s apartment with her and my mother. Perhaps the idea was that a young child would somehow diffuse the tension between them, but the reality was that I was a captive witness to hours of raised voices and crying jags.

In the lulls between, my grandmother would sometimes reminisce about growing up in rural Nova Scotia in the late 1890s. One time, she ran away from her duties at home, and her brothers skipped school, so that they could splash in the Annapolis. Her father left her to man the family sawmill when he had to go into town, and she learned to work the machinery on her own. She hopelessly knotted her hair around the tortoiseshell comb the first time she put up her long hair, without a mother or female relative to guide her.

Each time my grandmother opened a story, my mother interrupted. “I’ve heard that story a thousand times, Mother,” she said. “A thousand times!”

There was a great explosion up in Halifax, my grandmother said. The story, quickly swatted down by my mother, was somehow connected to a group of expatriate Nova Scotians my grandmother lived with in a Boston tenement. “A thousand times!” my mother interrupted.

I was eight or nine at the time, and had learned to bring a safe supply of books to pass the time. But how could the word “explosion” not grab my attention? I looked up. The two women glared at each other with tear-moist eyes, and my grandmother had already veered to her complaint that my mother was heartless and that she, my grandmother, was alone in the world without family or friends…

I licked my lips, hungry for the story. A great explosion, up in Halifax. But I couldn’t bring the conversation back to the explosion. Anytime I spoke, my grandmother’s face scrunched with irritation.

Later, on the long drive back to Maine, I sat wedged between my parents on the front bench seat of our car. A heavy haze of smoke hung against my face: my father smoked constantly during the seven or eight hours in the car that each weekend visit entailed, and he refused to crack the windows. My older siblings, squished together in the back seat, were just as miserable. My mother was still visibly upset over the visit. But I couldn’t help myself. I asked about the explosion in Halifax. “I don’t know anything about it,” my mother snapped. Her hands flicked through the smoke. “I can’t bear to listen to her.”

Years later, when I lived in Boston myself, I walked past the Prudential Center* daily, and every December a towering Christmas tree would raised. Hurrying to work in the morning, I didn’t have time to appreciate its beauty. But after dark, on the way home, I could see the glowing colors from blocks away, reflecting back and forth in the glass of the buildings.

The tree came from Nova Scotia, with thanks for Boston’s help after the Halifax Explosion of 1917. It took me several Christmases to make the connection.

Halifax in World War One

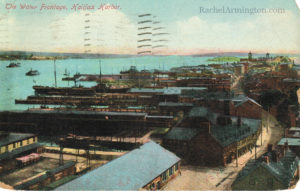

Halifax has a deep natural harbor that stays ice-free all year long. It’s also the closest port to Europe on the American continent. Halifax began as an English fort, forcing out the Mi’ kmaq and the French. The city had tight ties with Boston from the beginning. Many of the first buildings were built from timber shipped over from Massachusetts. When the Colonies broke away from Britain, many hoped and expected that Nova Scotia would become a state in the United States. But the province chose to stay with Britain.

Not only is Bedford Basin a deep and wide harbor, it has the added protection of The Narrows, where Halifax and Dartmouth come closer together.

The British Army manned the citadel capping the city, and the British Navy oversaw the dockyards, until a few years before World War One began. One ship acquired by the new Canadian Navy was the HMS Niobe, which the British Navy previously used in the Boer War. Because of its age and the repairs it required, the Niobe was decommissioned by 1914 and used as a depot ship in the harbor.

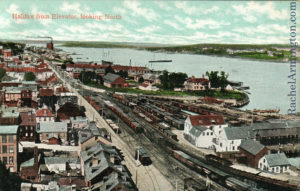

Halifax was an important port, and prospered during the war. Ports needed railways to carry cargo inland, and the city already had a strong system running from the piers, along the Bedford Basin, and further inland. Groundwork for an even larger station was in works closer to the entrance of the harbor.

In this postcard, trains line up near the piers. Dartmouth is in the upper right-hand corner. The Narrows are behind the factory with smoke pluming from its chimney, and Bedford Basin is beyond that.

The area near the Narrows was called Richmond, after the Virginian city Halifax traded with for sugar. Besides the sugar and cotton factories, there was wooden housing for the workers.

This street-view photo of a house on the corner of Acadia and Roome Street was taken in 1912, a few months after Alden and Jennie Lavers had it built. Their little daughter and her dog are sitting on the front steps. Their family was wealthy enough to build their own home. Alden Lavers was probably a mechanic of some kind: there are records of him being paid for fixing a motorcycle purchased for the police. The Lavers family survived the blast, but their house did not. The Nova Scotia Archives has a great map from the N.S. Board of Insurance Underwriters that shows what buildings were destroyed https://novascotia.ca/archives/explosion/archives.asp?ID=21

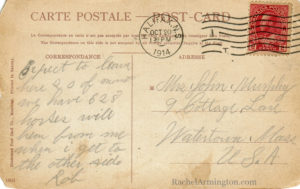

It’s easy to forget how people still relied on horses at the time of World War One. The military shipped thousands over to Europe. The Allies quickly learned that horses were no match against machine guns, but the animals were still crucial for moving supplies and machinery. Even so, the horses had a very short life expectancy after reaching the front.

The United States sold many horses to the Canadian military between 1914 and 1915.

A soldier mentioned the horses he’d be sailing with on the reverse side of this postcard, mailed from Halifax on October 20, 1914. “Expect to leave here 20 of month we have 628 horses will hear from me when I get to the other side, Rob”

Few Nova Scotians owned automobiles: the majority still depended on horses or oxen.

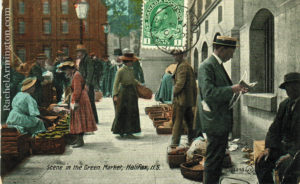

This postcard, mailed in October 1915, shows people buying fresh produce and artisan handwoven baskets in the Green Market. The photographer must have set his tripod down in the center of the walkway. It is such an intimate scene, with everyone busily shopping, but I suspect that the photographer must have posed at least some of the people. Cameras weren’t just carelessly snapped back then, and I doubt that the man in the straw hat would be so engrossed in his paper for that long.

The green postage stamp pasted near the top shows King George V, cousin to two other leaders in World War One, Tsar Nickolas II and Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Whereas the United States didn’t commit to the war until 1917, Canada was drawn in from the beginning in 1914. Although many Canadians weren’t too pleased that they were entering the war under Britain’s banner, the volunteer rate was high, particularly in Nova Scotia.

Back then, soldiers didn’t sign up for a limited time of service: unless they were seriously injured, they were in it to the (or their) end.

Here’s an excerpt from a 1916 letter my grandmother’s brother Ernest wrote to her about the trenches in France:

Dear Sister,

I received your ever welcomed letter a few days ago and am feeling all right now. I suppose I will be going back to my unit soon. My wounds are all well now. I do dread to go back into the trenches this winter. They are so bad. We have so much rain in this country. The mud is awful. I suppose we will have to walk through mud up to our hips again this winter…” (Ernest enlisted in 1914 and died in France in August, 1917.)

As more soldiers and supplies sailed over to Europe, Halifax added antisubmarine nets drawn across the mouth of the harbor. During the day, friendly ships could sail through a gate in the net, but at night the net was shut. If a ship didn’t make it inside the harbor before dark, it had to wait outside, at a higher risk of being attacked by a German submarine.

German submarines also added to the eventual decision of the United States to enter the war. The Germans sank the RMS Lusitania, which was carrying some passengers from the United States. The United States officially entered the war in April 1917.

Originally, the British Navy resisted organizing convoys to sail across the Atlantic. But to lessen the damage German submarines were causing, supply ships from Canada and the United States were grouped with British Navy cruisers, trawlers and submarines.

The Halifax Explosion

New York City was one of the ports where the convoys gathered. Towards the end of November 1917, the SS Mont-Blanc prepared to leave with a convoy headed for Europe.

The SS Mont-Blanc was an English-built, French-owned steamship ladened with explosives. In New York it was decided the ship was so slow that it would endanger the rest of the ships. So, the convoy sailed without her.

On December 1, 1917, the Mont-Blanc was directed to sail to Halifax in the hope it could join a convoy there that would better match its speed. But before the steamer could leave New York, the officials loaded more explosives, even to the point of stacking barrels on open decks.

Loaded with additional cargo, the steamer sailed even slower. Alone and on constant watch for German submarines, the Mont-Blanc sailed towards Halifax.

It arrived on December 5, too late to make it through the gate before the antisubmarine nets were closed for the night. After five days of anxiety, the captain and crew faced another long night outside of the protection of the harbor.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the net, another ship was almost as anxious to get out of the harbor.

The Imo was a Norwegian ship being used for as a Belgian Relief ship. The ship was headed for New York to be loaded with supplies. The Imo had been given clearance to leave on December 5, but had missed the closing of the gate after her shipment of coal hadn’t arrived in time.

The Mont Blanc sailed through the gate when it opened on the morning of December 6. Under the regulations of the time, ships needed to notify the port authorities if they would be loading or unloading explosives. But the Mont Blanc was only carrying explosives, not planning to load or unload them. So the ship wasn’t even flying flags to warn that it was carrying explosives.

Meanwhile, the Imo was steaming out of Bedford Basin. Trying to make up for lost time, the ship was sailing faster that it should within the harbor. Two ships sailing towards the Basin were in their wrong lane, which meant the Imo had to move into its wrong lane to avoid hitting them.

Now the Imo was right in the path of the Mont Blanc, which was in the correct lane for incoming ships. The Imo and the Mont Blanc blasted their horns at each other. Heavy as she was, the Mont Blanc couldn’t stop in time: light as the Imo was without the weight of cargo, she couldn’t maneuver as easily as she should.

When the Imo broke through their hull, the crew of the Mont Blanc shouted for them not to pull out. They knew that friction could send a spark onto the explosives. But either they didn’t hear, or didn’t understand, and the Imo pulled in reverse. Sparks flew onto the open deck of the Mont Blanc, where some of the barrels had been broken open by the collision. Within twenty minutes the growing conflagration would burst into a major explosion.

People on shore had heard the two ships blasting warnings at each other. Curious, people left their breakfasts to watch out the window. Many ran down to gather on the docks, not realizing that they should be running in the opposite direction. The Niobe sent out a boat to see if the crews needed any help.

Long before the boat from the Niobe was near them, the crew of the Mont Blanc saw that they were helpless to stop the blaze. Sinking the ship could put out the blaze, but there was no way they could fill the ship with water fast enough: they would need hours to do so, not minutes. Still shouting warnings to anyone they saw, they abandoned ship and rowed toward Dartmouth, where the blast flattened them on the beach.

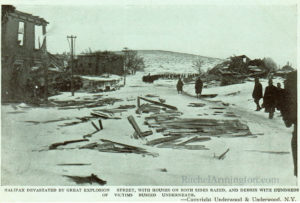

It was the largest man-made explosion in history until Hiroshima. Those closest to the white flash were vaporized. Almost two thousand people were killed outright and five times that were injured, including many blinded when their windows shattered. Richmond was wiped out. The people of Dartmouth suffered too, and the Mi’kmaw village in Tufts Cove was destroyed.

The blast threw the Imo to the Dartmouth shore. The Mont Blanc was completely torn apart, sending some parts as far as two miles away.

After the Blast

Although it may seem strange to us, disaster postcards were quite common at the time. But the same curiosity that makes us click on a link or compels us to repost a meme on social media is not so far removed from the need there was to share and collect disaster postcards.

Photos of mine and building collapses, train and plane wrecks, fires, floods, and tornados were printed on postcards or copied as real photo postcards.

Most of the photographs of the Halifax Explosion were probably not taken immediately, although there were plenty of professional photographers in the area. If there is snow in the photo, it was most probably taken later, after the approaching blizzard hit.

Survival and saving the injured was the priority. Halifax was cut off from communicating with the outside world. The railroad and the telegraph lines were destroyed.

The area hardest hit was Richmond. Homes were blown away or flattened. The wood from the houses fed the fires spreading from overturned lanterns and coal stoves.

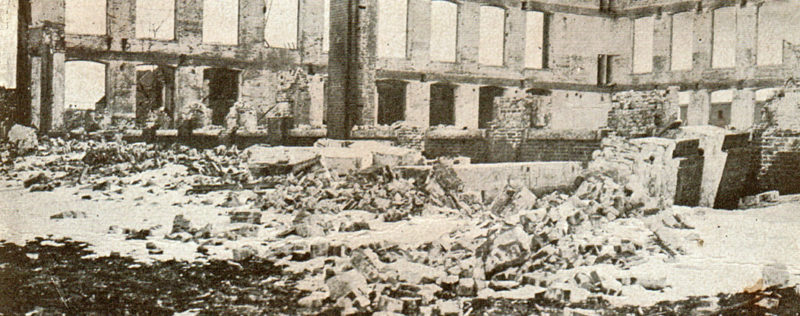

Factories couldn’t withstand the explosion either.

Many people, living or dead, were trapped under the rubble. The hospitals were overwhelmed with the injured and soon ran low on medicine and supplies.

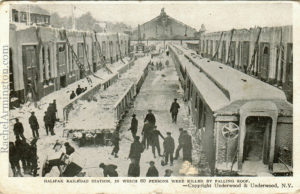

The glass roof of the train station shattered under the pressure of the blast. Travelers waiting for trains at the time of the explosion were killed by falling glass.

Despite the damage to the telegraph lines, a few messages had been sent out, including one to Boston. Rescue trains from Atlantic Canada quickly made their way as close to the city as they could, even though the rescue personnel had to walk into Halifax once they reached the edges of the destruction.

Soldiers, who had been preparing to ship out, now found themselves rescuing people in a landscape that many compared to the war-ravaged areas of France.

This close-up of the above postcard is interesting because the photographer hand-drew lines directly on the printing plate so that the two standing soldiers would be more visible against the rubble.

Haligonians were just as heroic, and perhaps surprisingly, incredibly organized in the face of disaster. Five years earlier, when the Titanic has sunk, Halifax had been crucial in searching for and retrieving the victims.

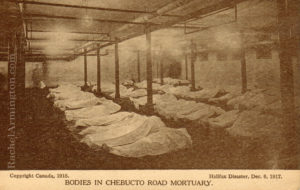

After the blast, residents quickly stepped in and organized how to distribute supplies, house homeless, and keep track of the injured and dead. Many victims didn’t have any form of identification on them.

A morgue was sent up in the basement of the Chebucto School, which was far enough from the blast to have only minor damage.

Despite this destruction caused by the man-made explosion, nature was about the cause more havoc. Snow began to fall.

The blizzard dropped 16 inches of snow over the city. The snow brought down the telegraph lines that had been hastily repaired after the blast. Many horses had died in the blast, so there weren’t enough to plow the streets, even if they had been cleared of rubble. The military set up tents for the newly homeless. The blast had knocked out so many windows and damaged the structural integrity of so many homes, that there was a shortage of safe buildings.

The heavy snow buried the railroad tracks. The plows on the front of incoming rescue trains couldn’t push off enough snow. The rescue personnel had to get out and shovel. One of those trains–full of doctors, nurses, and tons of medical supplies–was from Boston. The first train had been organized, loaded and set off within 13 hours of the blast, and would reach Halifax within 48 hours. The next train from Boston brought 70 nurses, 30 doctors and complete operating theaters.

Although Boston had a special connection with Halifax, people all over the United States immediately donated and set relief efforts into action. Warehouses were set up to store donated furniture, bedding, kitchenware and lumber for the time when the people of Halifax could start rebuilding.

Even though my grandmother was critical and harsh when I knew her, I’m certain that she stood in line with other Bostonians in the relief line, to donate some spare garment or a portion of her factory wage to help the people of Halifax.

The rebuilding took years. The ties between Boston and Halifax stayed strong: even though Halifax was still in crisis from the Explosion, the city sent nurses and doctors to Boston during the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918. But a hundred years later, I wonder how many Bostonians really contemplate that connection when that tree of gratitude is trucked down from Nova Scotia. I just hope people remember that it’s more than just a Christmas tree.

*The yearly Christmas tree is installed on the Common now instead of the Pru Center.

All of the postcards and photos shown on this website are from my personal collection.